An Update on the REPO Market

From our latest Quarterly Economic Commentary and Review… (1st Quarter 2020)

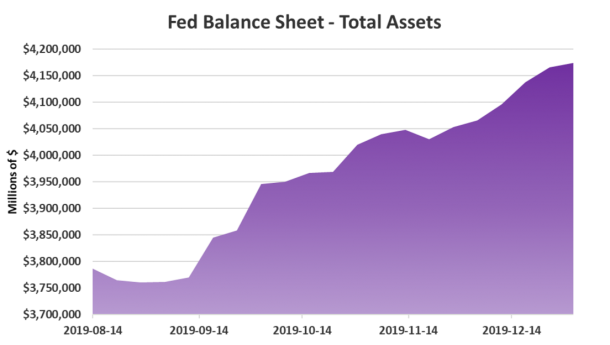

Back in September, there was a mini-crisis within the Repo Market. We discussed the details of what occurred in the 4th Quarter 2019 Economic Commentary. Since then there has been a concerted effort by the Fed to ensure that the end-of-quarter and end-of-year liquidity requirements would be sufficient. As a result, the Fed has embarked on a rather aggressive plan that has continued to push funds into the short-term lending markets. To be clear, the term “aggressive” doesn’t quite describe the lengths that they have gone to over the past few months.

For perspective on this, we only need to look back to the actions taken during the worst days of the financial crisis. We know that the Fed was buying upwards of $80 billion of Treasuries per month at that time. Through the quantitative easing program (money printing) they were able to effectively keep rates low and add the necessary liquidity to markets. The idea was to promote the wealth-effect by allowing risk assets (stocks, commodities, etc.) to rise as excess monies flowed into the system. The Fed hypothesized that by flushing funds into markets, portfolio values would swell and result in higher investor and consumer confidence.

Essentially, the wealth-effect is a behavioral economic theory suggesting that people spend more as the value of their assets increase. The idea is that consumers feel more financially secure and confident about their wealth when their homes and/or investment portfolios increase in value. The Fed was able to create that much-needed confidence by combining lower lending rates and quantitative easing. Markets rallied off of the lows and a new economic expansion cycle was born.

Fast forward to 2018. The Fed then decided that since the employment situation was strong, and the economy was doing exceptionally well it was time to reverse its actions. Rates were scheduled to rise, and their balance sheet would start to shrink. By the end of 2018, markets began to lose confidence that the Fed would have their backs and thus, we saw a rapid destruction of risk assets in the 4th quarter. It was only when Fed Chair Powell announced that they would reverse course that asset prices begin to rise. Essentially, the Fed began a new rate cutting cycle, but they didn’t shift their position on quantitative easing (balance sheet reductions).

That all changed with the REPO market scare of September 2019. While the Fed made it abundantly clear that they were not embarking on a new QE program, they started to increase the size of the balance sheet through bond purchases. It looked very much like QE, but somehow, we were supposed to believe that it wasn’t.

The result? An average of $125+ billion per month was added to the Fed’s balance sheet during the last few months of 2019 (See chart on previous page). This far exceeded the $80 billion per month that was added during the financial crisis. Concurrently, there was a ramp higher for risk-assets. In fact, during the Non-QE QE period, equity markets around the world experienced impressive growth, stretching U.S. equity valuations to levels not seen in years.

Have a question? Want more information? ASK ANDREW

We will also send you the full commentary each quarter.