Bloomberg Markets had a very informative and lengthy article about the growing concern over new strains of diseases that are not able to be controlled with current medications.

`THERE IS A TSUNAMI THAT‘S GOING TO HAPPEN IN THE NEXT YEAR OR TWO WHEN ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE EXPLODES,‘ DR. GHAFUR SAYS.

Read on.. (click images to enlarge)

Poor hygiene has spread resistant germs into India‘s drains, sewers and drinking water, putting millions at risk of drug-defying infections. Antibiotic residues from drug manufacturing, livestock treatment and medical waste have entered water and sanitation systems, exacerbating the problem. As the superbacteria take up residence in hospitals, they‘re compromising patient care and tarnishing India‘s image as a medical tourism destination. “There isn‘t anything you could take with you traveling that would be useful against these superbugs,” says Robert Moellering Jr., a professor of medical research at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

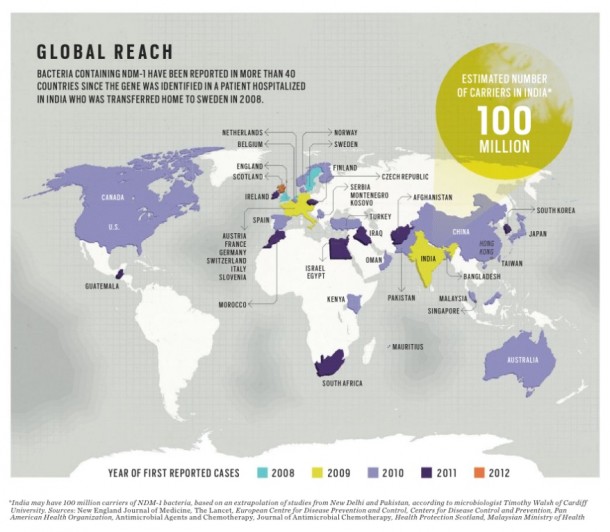

The germs””and the gene that confers their heightened powers””are jumping beyond India. More than 40 countries have discovered the genetically altered superbugs in blood, urine and other patient specimens. Canada, France, Italy, Kosovo and South Africa have found them in people with no travel links, suggesting the bugs have taken hold there.

Drug resistance of all sorts is bringing the planet closer to what the World Health Organization calls a post-antibiotic era. “Things as common as strep throat or a child‘s scratched knee could once again kill,” WHO Director-General Margaret Chan said at a March medical meeting in Copenhagen. “Hip replacements, organ transplants, cancer chemotherapy and care of preterm infants would become far more difficult or even too dangerous to undertake.”

Already, current varieties of resistant bacteria kill more than 25,000 people in Europe annually, the WHO said in March. The toll means at least 1.5 billion euros ($2 billion) in extra medical costs and productivity losses each year. “If this latest bug becomes entrenched in our hospitals, there is really nothing we can turn to,” says Donald E. Low, head of Ontario‘s public health lab in Toronto. “Its potential is to be probably greater than any other organism.”

The new superbugs are multiplying so successfully because of a gene dubbed NDM-1. That‘s short for New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase-1, a reference to the city where a Swedish man was hospitalized in 2007 with an infection that resisted standard antibiotic treatments. The superbugs are proving to be not only wily but also highly sexed. The NDM-1 gene is carried on mobile loops of DNA called plasmids that transfer easily among and across many types of bacteria through a form of microbial mating. This means that unlike previous germ-altering genes, NDM-1 can infiltrate dozens of bacterial species. Intestine-dwelling E. coli, the most common bacterium that people encounter, soil-inhabiting microbes and water-loving cholera bugs can all be fortified by the gene. What‘s worse, germs empowered by NDM-1 can muster as many as nine other ways to destroy the world‘s most potent antibiotics.

NDM-1 is changing common bugs that drugs once easily defeated into untreatable killers, says Timothy Walsh, a professor of medical microbiology at Cardiff University in Wales. Or as in Skaret‘s case, the gene is creating silent stowaways poised to attack if they find a weakness””or that can pass harmlessly when the body‘s conventional microbes win out. Cancer patients whose chemotherapy inadvertently ulcerates their gastrointestinal tract are especially vulnerable, says Lindsay Grayson, director of infectious diseases and microbiology at Melbourne‘s Austin Hospital. “These bugs go straight into their bloodstream,” Grayson says. Newborns, transplant recipients and people with compromised immune systems are at higher risk, he says. Six infants died in a small hospital in Bijnor in northern India from April 2009 to August 2010 after NDM-1 containing bacteria resisted all commonly used antibiotics.

India is susceptible because it has many sick people to begin with. The country accounts for more than a quarter of the world‘s pneumonia cases. It has the most tuberculosis patients globally and Asia‘s highest incidence of cholera. Most of India‘s 5,000-plus drugmakers produce low-cost generic antibiotics, letting users and doctors switch around to find ones that work. While that‘s happening, the germs the antibiotics are targeting accumulate genes for destroying each drug. That enables the bugs to survive and proliferate whenever they encounter an antibiotic they‘ve already adapted to.

India‘s inadequate sanitation increases the scope of antibacterial resistance. More than half of the nation‘s 1.2 billion residents defecate in the open, and 23 percent of city dwellers have no toilets, according to a 2012 report by the WHO and Unicef. Uncovered sewers and overflowing drains in even such modern cities as New Delhi spread resistant germs through feces, tainting food and water and covering surfaces in what Dartmouth Medical School researcher Elmer Pfefferkorn describes as a fecal veneer. Germs with the NDM-1 gene existed in 51 of 171 open drains along the capital‘s streets and in two of 50 samples of public tap water, Walsh found in 2010.

Abdul Ghafur, an infectious diseases doctor in Chennai, southern India‘s largest city, sees patients every week who suffer from multidrug-resistant infections. He and others who used to successfully combat infections with such common antibiotics as amoxicillin now must use more-expensive ones that target a broader range of germs but typically cause greater side effects. Some infections don‘t respond to any treatment, evading all antibiotics, he says.

That‘s bad news because the more frequently the NDM-1 gene is inserted into different bacteria, the more likely it will enter virulent forms of E. coli, sparking outbreaks that may be impossible to subdue, says David Livermore, who heads antibiotic resistance monitoring at the U.K.‘s Health Protection Agency in London.

The gene may even spread to the microbial cause of bubonic plague, the medieval scourge known as Black Death that still persists in pockets of the globe. “It‘s a matter of time and chance,” says Mark Toleman, a molecular geneticist at Cardiff University. Plasmids carrying the NDM-1 gene can easily be inserted into the genetic material of Yersinia pestis, the cause of plague, making the infection harder to treat, Toleman says.