Over the course of many years, we were led to believe that relying on economic data out of China was a fool’s errand. While we all witnessed the incredible growth of the Chinese real estate market, we eventually found out that it resulted in hundreds of miles of empty apartment complexes. These were built on barren land sites in remote parts of the country during the mid-2000s and were commonly referred to as “Ghost Cities”. All the while, local government officials were lining their pockets with payoffs and hush money in an effort to keep the expansion machine rolling along.

It wasn’t long for satellite imagery to confirm our worst fears. Ghost Cities were being erected solely for the purpose of the domestic growth initiative. Essentially, this was a ruse to bloat the bird – making it appear as though there was significant productivity and organic growth. To put it into perspective; people were hard at work erecting vacant skyscrapers while there was no intention of them ever being occupied. In the short run, this proved to be beneficial to the domestic economy. However, it would require government funding to keep the zombie projects alive.

In a sense, this was one of the greatest Keynesian experiments of all time.

Keynesian Economics:

“Keynesian Economics focuses on using active government policy to manage aggregate demand in order to address or prevent economic recessions.

Keynes developed his theories in response to the Great Depression, and was highly critical of classical economic arguments that natural economic forces and incentives would be sufficient to help the economy recover.

Activist fiscal and monetary policy are the primary tools recommended by Keynesian economists to manage the economy and fight unemployment.” Investopedia.com

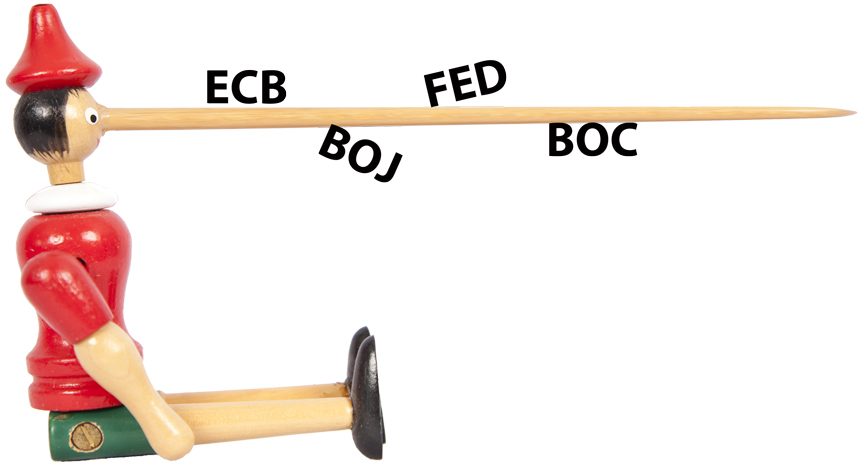

The problem is that it turned out to be a gigantic illusion. Once the attractive outer falsehood was removed, the grotesque inner reality was revealed. The entirety of China’s growth was contrived and simply propped up by massive governmental spending.

What followed was a general disbelief in most, if not all, of the official reports that came out of China. In turn, this forced analysts and economists to rely on alternative measures of activity, like energy consumption and non-governmental “unofficial” research reports.

To this day there is still a good deal of skepticism when it comes to the official economic data out of China. How is it that such a large country with thousands of datasets and a significant rural population somehow meets, almost exactly to the penny, every economic estimate? Pretty darn amazing!

Then there is the EuroZone. When economic times get really dreadful, it seems that both politicians and the ECB are very comfortable with just saying whatever needs to be said to keep confidence up. Recall that the fix for all financial woes in the region has been to simply paper it over with money. The ECB has tried to cover up the systems mounting debt with experimental monetary policy including a spectacular amount of asset purchases. Unfortunately, although not surprisingly, this has resulted in waltzing the region’s banks to the financial crematorium. While the ECB is performing similar actions as the Federal Reserve once did, the general consensus is that the ECB was too slow in implementing their tools.

There is no way that we can leave Japan out of this discussion. Prime Minister Shinz? Abe was elected with “three arrows in the quiver” as the base of what was called, Abenomics. His plan was to boost Japan’s economy and the stubborn deflationary conditions that had/has been ever-present for decades. Similar to China, the government started its stimulus program, hoping the excess would pull the economy out of its terminal malaise. Over time, interest rates dropped into negative territory, the Yen careened lower and the stock market rallied. As the real economy failed to show any signs of sustainable growth, more stimulus was added.

Since buying record amounts of debt didn’t do the trick, Abeonomics needed to transform further. The next big idea was to move the stock market up as a way to increase wealth (another dull arrow?). The Bank of Japan (BOJ) went in and directly purchased Japanese securities in the open market.

According to recent reports, the BOJ holds over 28 trillion yen ($250 billion) in exchange-traded funds as of the end of March 2019 — 4.7% of the total market capitalization of the first section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange.

Assuming that the bank maintains its current target of 6 trillion yen in new purchases a year, its holdings would expand to about 40 trillion yen by the end of November 2020. This would place it above the Government Pension Investment Fund’s TSE first-section holdings of more than 6%.

The result? Inflation hasn’t budged and the Japanese economy is still running at a sub-optimal pace. However, they keep professing that it will get better and will continue to fund “growth programs” with debt and asset purchases.

What about here, back at home? Due to “checks and balances”, the one region that we had been led to think data would be truthful and accurate, was the United States. We have been conditioned to trust that the Fed understands the economy and has predictive models that are well honed. While knowing that statistics can often be manipulated in a way that benefits the outcome, it was assumed that all reporting was being done by the book. No excess added or detracted, just the facts and only the facts.

Then, in 2016 the new administration was installed along with their theory that the stock market would be the best gauge of their success. Economic prosperity will heal all ills is the motto. A replay of what we saw in Japan, China, and Europe over the past decade(s).

Even though the U.S. financial system appears to be on solid footing after a long transformation process, the need to get the stock market higher and yields lower at any cost are very apparent. Whatever it takes, no matter how twisted the tale, the ends will justify the means.

While we all want wealth and a retirement free of financial worry, we also need to ensure that the path is sustainable. Overburdening the system for short-term gain is not the path to long-term success.

Here is the bottom line: Pinocchionomics has no place in the global economy. Cutting corporate taxes to boost earnings at the risk of overleveraging the system cannot be sustained over the long haul.

It’s about time that central banks and politicians realize that short-term thinking will only manifest itself into the next financial crisis. Regrettably, this change of philosophy may never happen as political cycles, the desire for power and unrelenting greed have turned markets into playgrounds for governmental stalwarts.

While one swamp is being drained another radioactive waste infested marsh is being constructed.