Cycles Pulled Forward

Bullish U.S. Cycle

“History doesn’t repeat itself but it often rhymes“ – Mark Twain

Cycles are an economic reality. Sometimes they are short, sometimes they extend a bit longer than expected. But, more often than not, it is the same story that we see play out time and time again. For example, analysts get a hold of a bullish argument about one thing or another and they press it hard. Like penguins jumping into a body of water, once the first one has enough courage to take the plunge, the rest follow enthusiastically.

Just about a year ago, we saw that there was a chorus of bullish sentiment focused on non-U.S. markets. Almost without que[gview file=”https://thedisciplinedinvestor.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/HC_EcoCommentary_4Q2018-1.pdf”]stion, most analysts believed that there was a strong reason to reduce U.S. equity exposure and overweight foreign assets. They had plenty of reasons lined up as well, sighting relative valuations, currency weakness and central bank divergence. At the time, we viewed this “universal truth” with a great deal of skepticism.

Part of our reasoning was that the arguments were somewhat thin. The consensus was built on a simplistic view based on relative valuation. On one hand, we agree there may be some merit to the concept of a mean-reversion trade. Since non-U.S. assets were underperforming, valuations were considered cheap and many analysts viewed this as attractive. However, there usually needs to be a catalyst to provide some reasonable lift to the underperforming sector/asset. In other words, it requires a change in the factors that are supporting the outperformance and/or overvaluation in order for this to yield a beneficial outcome.

In the 2nd Quarter 2017 Economic Commentary we wrote:

Essentially, the lower relative P/E’s and a very easy monetary policy is the core reasoning that many of the talking heads have been pushing the idea that non-U.S. equities should be an overweight position. At the same time, some have even been looking to reduce U.S. equity exposure as valuations are hitting highs not seen in many years.

Not much has changed over the past year when we look at the general direction of rates for the

U.S. and the rest of the world. At the same time, there was one important factor that provided a noteworthy benefit for U.S. equities: An enormous tax cut for corporations which helped boost earnings. That one feature created a major benefit for U.S. stocks. The comparative valuation argument was now in trouble. Even as the divergence in monetary policy should have been beneficial for foreign stocks, the tax cuts tilted the equation dramatically in favor of U.S. equities. This, in conjunction with the removal of accommodative monetary policies caused the U.S. Dollar to strengthen appreciably. That lead to a general devaluation of assets priced in foreign currencies.

This is why we were doubtful that the simple comparison of P/E ratios would lead to a substantial benefit for non-U.S. equities – as we wrote:

While there has been a resurgence of confidence in equity markets, the fact that the P/E ratios within Eurozone markets are much lower may have more to do with the outlook than anything else. Simply taking a relative comparison of an overvalued market to ones that are fairly valued may not be the smartest investment idea ever conceived.

In reality, the recent tax reform helped to instill a great deal of confidence that there was the potential for U.S. corporate earnings to grow at double-digit rates for the next 12-24 months. Even with the strong headwinds related to Fed tightening, the new corporate tax rate of 21% has been enough to offset these concerns. As Europe (and other central banks) continued to utilize blunt measures in an attempt to push asset prices higher, their currency values slipped against the U.S. Dollar. That currency weakness should have been supportive of risk assets – however, the reality is that it backfired.

Yes, backfired with a backstory… Over the past decade, debt was the main form of economic fuel that was perceived as the best way to support economic expansions. Many foreign countries issued dollar-denominated notes as a means to bolster inflows. As the U.S. Dollar increased in value against the currencies of countries issuing these bonds, it became more difficult over time to properly fund payback options. Here is one simple rational: As the base currency fell, repayment in U.S. dollars became much more expensive. As time went on and there was no reprieve from a rising U.S. Dollar, foreign central banks no longer had the luxury of adding liquidity or lowering rates as this would essentially exacerbate the problem.

Over the past year, this is part of the reason that several currency crises have cropped up. Countries that had weak economies to begin with were now in a battle to save their currency from a meltdown. If they raised rates, they would slow the economy. If they lowered rates it would potentially devalue the currency even further. Essentially, they have been between a rock and a hard place. Nothing they could do was able to rectify the situation in their favor. Additional bond issuance was off the table and doing nothing was also problematic.

Looking at this objectively, it was a lose-lose- lose-lose situation. Little could be done that could rescue them from a very dire situation. On top of that, the relative valuation argument was now all but dead since the tax cuts changed the equation to a point where the valuation differential tightened immensely.

Is it any wonder why emerging markets and non-U.S. equities have been out of favor considering these points? The fact that U.S. economic growth continues to be on a positive trajectory and corporate earnings are on solid footing has instilled a great deal of confidence with investors.

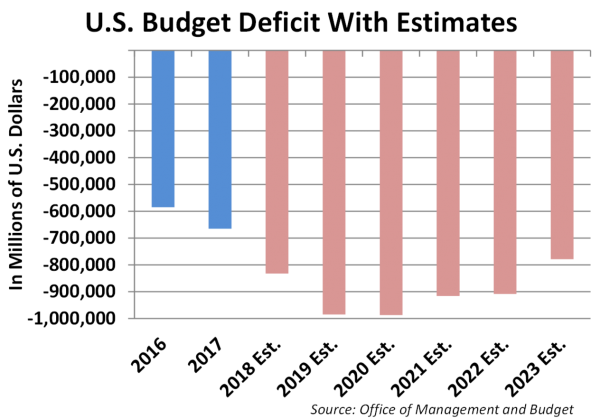

Now we ponder: “What will it will take to bring investors back toward non-U.S. investments?” The answer may be found if/when the U.S. Dollar weakens – and there is one potential way for this to occur…swelling deficits.

For all of the good that the tax cuts have done for U.S. markets, there is a matter that needs to be addressed. While it was supposed to be an all-around benefit for the U.S. economy, the tax cuts have also caused a sharp reduction in tax receipts. In turn, this is causing an enormous bump in the deficit. As can be expected, there are a few government projections that show an increase in the tax base. However, it does not appear that there will be enough to offset the current spending requirements provided in the latest budget.

Here is why:

The Trump administration will set new records for defense spending. It is estimated to reach $874.4 billion in 2018 and $886 billion in 2019.

Spending on Social Security, the largest federal program today, will surge by 77 percent, from $845 billion in 2014 to $1.5 trillion in 2024. Medicare is the largest health care program and its spending will surge by 72 percent, from $603 billion in 2014 to $1.04 trillion in 2024.

On top of record defense spending and a jump in mandatory spending on entitlements, the tax cuts are estimated to increase the deficit by close to $1 trillion over the next decade.

Here is how this could playout: If the deficit continues to grow inline with projections, the U.S. dollar should weaken. Higher deficits are also negative for a country’s debt rating. U.S bond prices could deteriorate in advance of a potential credit downgrade of U.S. government debt – just as was the case in 2011 when Standard & Poor’s voiced concern over an oversized expansion of the deficit and moved its rating down one notch to AA+ from AAA.

If there is the threat of a credit downgrade, it may force the U.S. to consider spending cuts over time. That could be an important moment for global markets, eventually leveling the playing field and benefiting non-U.S. equities after some initial chaos. While this is all speculation at this time, it is an important consideration with overloaded debt levels and a deficit that is at historical levels – and growing daily.

In the end, it is worth concluding with the notion that it may take a fundamental shift other than just valuations or a simple reversion to the mean in order to get non-U.S. assets performing again. As for now, the overarching factors support a strong U.S. dollar and economy for the near-term, which in turn may continue to favor U.S. securities.

Pull-Forward Effect

“A nickel ain’t worth a dime anymore.“ – Yogi Berra

When items are cheap or on sale, it often piques the interest of a shopper. Right then and there a choice is being presented; As a consumer of that product, do we decide to buy it now (since it is more affordable) or perhaps wait a bit to see if the price moves any lower? Within the decision-making process, purchasing a product will depend on how deep the discount is and one’s actual need for the good or service.

In contrast, if we notice that prices are rising, we will often act quickly in order to lock in the price before it becomes unaffordable. In fact, depending on how rapidly prices are escalating, we may look to load up on some items in a big way, even if we do not have an immediate need. As long as we pay lower prices today for something that we will need in the future, it makes good economic sense.

In contrast, if we notice that prices are rising, we will often act quickly in order to lock in the price before it becomes unaffordable. In fact, depending on how rapidly prices are escalating, we may look to load up on some items in a big way, even if we do not have an immediate need. As long as we pay lower prices today for something that we will need in the future, it makes good economic sense.

As an example, let’s consider a situation where you use a specific item on a regular basis. For our illustration, let’s just call them doohickeys. From what you can tell, you have no reason to believe that there will be a change in your needs in the near future for doohickeys. One day, you find out that all doohickey pricing will be going up by 20% within a month’s time. This information will probably bring you to the realization that you should buy a supply to avoid the future price increase. Since you don’t know how long the prices will stay elevated, or if this is the end to the price increase cycle, you will probably stock up in a big way. It’s only natural.

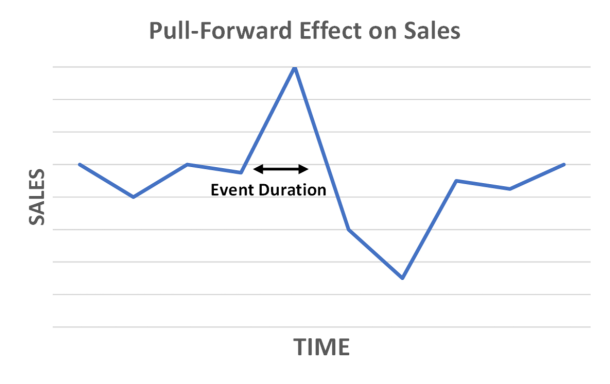

This condition can aptly be termed the Pull-Forward Effect.

In the time preceding a widely telegraphed price surge, buyers may be on the hunt for products that will incur a price increase. Whether it is a consumer or a manufacturer, there is a strong reason to obtain inventory ahead of the rise in price.

The Pull-Forward Effect has occurred before and it may be happening now. Looking back, there was a recent time in history that can be used as a comparable analog and model. In late 2013, the Japanese government announced a steep increase in the country’s retail sales tax rate that was to be implemented in 2014. Consumers were apprised well in advance of the hike and in response, they opened up their wallets and went on an epic buying spree. After they were stuffed with goods – the buying stopped, just ahead of the date of the tax increase. It wasn’t a random occurrence. The noticeable change in consumer spending was ell correlated with the date of announcement and the date of the tax increase. In fact, an additional tax increase was announced for 2015 and the exact same thing happened.

“I’ll gladly pay you Tuesday for a hamburger today.“ – Wimpy –

The chart of Japan’s Retail Sales clearly illustrates how this played out over the two event cycles.

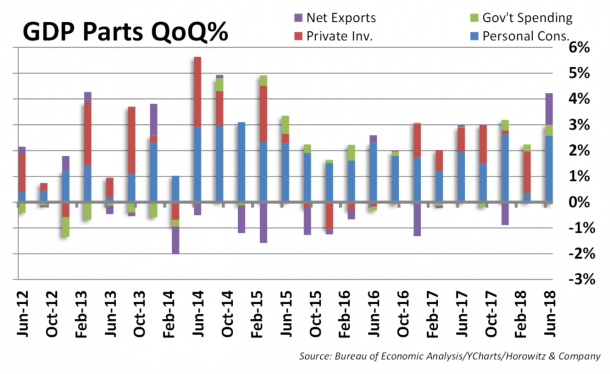

A similar event cycle may be occurring today in the U.S. This time it relates to tariffs. With pre-announcements of potential tariffs starting in 2018, many consumers and companies believed that stocking up on goods ahead of the actual implementation could be a smart plan. In turn, manufacturing picked up, inventory levels rose, and retail sales increased. This all had a positive impact on GDP, which clocked in above 4% for the first time in years. We are now looking for hints that the Pull-Forward Effect may have negative implications for economic growth

In turn, manufacturing picked up, inventory levels rose, and retail sales increased. This all had a positive impact on GDP, which clocked in above 4% for the first time in years. We are now looking for hints that the Pull- Forward Effect may have negative implications for economic growth in the future.

With rolling implementation dates for tariffs against many countries, the event timing may also be extended. For the time being, it will theoretically help to keep GDP at higher levels for the next quarter or two. The problem is that a sharp slowdown may follow on the backend – just like was observed in Japan. While the exact timing is not clear, in all likelihood, economic activity the first quarter of 2019 may show a marked slowdown.